Lebesgue Integration and L2 functions

Every piecewise continuous function is Riemann integrable. Lebesgue integral can handle a very large class of functions, including all the Riemann integrable functions, but also even very discontinuous functions. In fact, it’s safe to say that it can integrate any function that one actually needs in mathematics in real-life applications.

The passage from Riemann’s theory of integration to that of Lebesque is a process of completion. It is of the same fundamental importance in analysis as is the construction of the real number system from the rationals.

Lebesgue Measure

I have to pay a certain sum, which I have collected in my pocket. I take the bills and coins out of my pocket and give them to the creditor in the order I find them until I have reached the total sum. This is the Riemann integral. But I can proceed differently. After I have taken all the money out of my pocket I order the bills and coins according to identical values and then I pay the several heaps one after the other to the creditor. This is my integral.

————Lebesgue summarized his approach to integration in a letter to Paul Montel

Whenever the Riemann integral exists (i.e.,the limit exists), the Lebesgue integral also exists and has the same value.

The familiar rules for calculating Riemann integrals also apply for Lebesgue integrals.

For some very weird functions, the Lebesgue integral exists, but the Riemann integral does not.

There are also exceptionally weird functions for which not even the Lebesgue integral exists.

Lebesgue measure

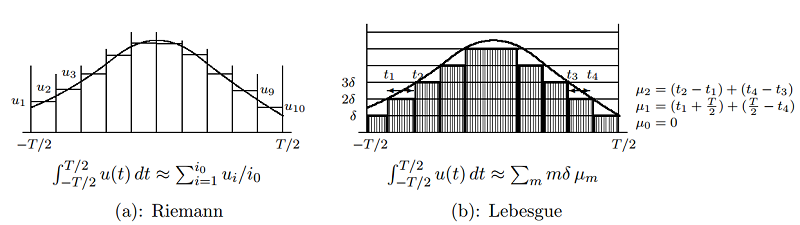

In Lebesgue integration, the measure \(\mu_m = \{ t : m\delta \le u(t) \lt (m+1)\delta \}\) is called Lebesgue measure.

For any real \(a \le b\), including \(a = -\infty\), \(b = \infty\), the interval \(I = (a, b)\) has measure \(\mu(I) = b − a\). Same if either or both end points included.

The measure of a finite union, \(I_1,\dotsc,I_k\) of disjoint intervals is the sum of the measure of those intervals, \(\sum_{j=1}^k \mu(I_j)\).

The measure of a countable union \(I_1,\dotsc,I_k\), of disjoint intervals is \(\mu(\cup I_j)=\lim_{k\rightarrow\infty} \sum_{j=1}^k \mu(I_j)\).

Any countable set of real numbers has zero measure.

Out measure

We need more than countable unions of intervals for a viable integration theory.

If \({\cal B}\) is measurable, we also need its complement, \(\overline {\cal B}\), to be measurable with \(\mu ({\cal B}) = T − \mu (\overline{\cal B})\).

Define the outer measure \({\mu}^{\circ} ({\cal A})\) of any set \({\cal A}\) as

Measurable and measure

A set \({\cal A}\) (over \([−T/2, T/2]\)) is measurable if \({\mu}^\circ ({\cal A})+{\mu}^\circ (\overline{\cal A}) = T\).

If \({\cal A}\) is measurable, then its measure, \({\mu}({\cal A})\), equals \({\mu}^\circ ({\cal A})\).

Each measurable set has a measurable complement.

If \({\cal A} \subset {\cal B}\) are both measurable, then \(\mu ({\cal A}) \le \mu ({\cal B})\).

Any measurable set can be approximated arbitrarily closely by a cover.

Lebesgue measure for a union of intervals

Let \({\cal A}_1, {\cal A}_2,\dotsc\) be any sequence of measurable sets. Then \({\cal S} = \bigcup_{k=1}^\infty {\cal A}_k\) and \({\cal D} = \bigcap_{k=1}^\infty {\cal A}_k\) are measurable.

If \({\cal A}_1, {\cal A}_2,\dotsc\) are also disjoint, then \(\mu (\cal S) = \sum_k \mu ({\cal A}_k)\).

If \({\mu}^\circ ({\cal A}) = 0\), then \({\cal A}\) is measurable with measure 0.

Lebesgue Ingegration

Measurable functions

A function \(\{ u(t) : \mathbb{R}\rightarrow\mathbb{R}\}\) is measurable if \(\{ t : u(t) \lt b \}\) is measurable for each \(b\in \mathbb{R}\).

The Lebesgue integral exists(with perhaps an infinite value) if the function is measurable and if the approximation to the Lebesgue integral has a limit as the vertical interval size \(\delta\) goes to 0.

Sets of measure zero do not effect the integral.

A complex function \(\{ u(t) : [−T/2, T/2]\rightarrow\mathbb{C} \}\) is measurable if both \(\Re [u(t)]\) and \(\Im [u(t)]\) are measurable.

\(L^2\) Functions over \([−T/2, T/2]\)

\(L^1\) functions

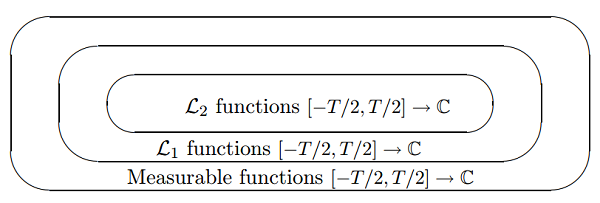

A function \(\{ u(t) : [−T/2, T/2]\rightarrow\mathbb{C}\}\) is said to be \(L^1\), or in the class \(L^1\), if \(u(t)\) is measurable and the Lebesgue integral of \(|u(t)|\) is finite.

\(L^1\) functions are sometimes called integrable functions.

\(L^2\) functions

A function \(\{ u(t) : [−T/2, T/2] \rightarrow \mathbb{R} \}\) or \(\{ u(t) : [−T/2, T/2] \rightarrow \mathbb{C} \}\) is said to be an \(L^2\) function, or a finite-energy function, if \(u(t)\) is measurable and the Lebesgue integral of \(|u(t)|^2\) is finite.

If \(\{ u(t) : [−T/2, T/2]\rightarrow\mathbb{C} \}\) is \(L^2\), then it is also \(L^1\).

Reference:

- Robert G.Gallager. (2009). Principles of Digital Communication (New York: Cambridge University Press).

- Terence Tao. (2009). Analysis I. Analysis II (Hindustan Book Agency)

- Walter Rudin. (1987). Real and complex analysis (McGraw-Hill Book Company)

- Siegmund-Schultze, Reinhard (2008), Henri Lebesgue, in Timothy Gowers, June Barrow-Green, Imre Leader, Princeton Companion to Mathematics, Princeton University Press.

- Prof. Robert Gallager. (2006). 6.450 Digital Communication. MIT OpenCourseWare (http://ocw.mit.edu/)

A good person! More about the author →