Fourier Series

Roughly speaking, the theory of Fourier series asserts that just about every periodic function can be decomposed as an(infinite) sum of sines and cosines (trigonometric polynomials). Periodic waveforms are not very interesting for carrying information; after observing one period, the rest of the waveform carries nothing new. Our interest here is almost exclusively in time-limited waveforms.

Linear Time-Invariant System

If \(O\{ x(t) \} = y(t)\),

Linearity(Additivity and Homogeneity) :

Time-invariance :

Why play a fundamental role

- Many communication channels possess LTI property.

- We hope the channels can be approximated as LTI or extended from LTI in a range of applications.

More explanation about the sencond item:

- Unit-sample response \(h[n]\) or unit-impulse response \(h(t)\) is a complete description of an LTI system.

- Many systems are naturally described by their frequency response; LTI systems can be characterized by responses to eternal sinusoids; frequency response is easy to calculate from the system function.

- Sinusoidal and complex exponential signals are used to describe the characteristics of many physical processes, in particular physical systems in which energy is conserved. Periodic complex exponentials serve as extremely useful building blocks for many other signals(harmonic). If the input to an LTI system is expressed as a linear combination of periodic complex exponentials or sinusoids, the output can also be expressed in this form, with coefficients that are related in a straightforward way to those of the input.

- For many physical channels, they introduce distortions in their passbands, such a channel can be modeled by an LTI filter followed by AWGN noise, the approach to remove ISI(inter-symbol interference) is usually known as equalization.

- Linear operations preserve Gaussianity.

- A large class of interesting functions(\(L^2\)) could be represented by linear combinations of complex exponentials(Fourier Theorem).

Fourier Series

Given in most engineering texts

The Fourier series for function \(\{ u(t) : [-T/2, T/2] \to \Bbb{C} \}\) is given by

Electrical engineers formerly reserved the symbol \(i\) for electrical current and thus often use \(j\) to denote \(\sqrt{-1}\). The Fourier series of a time-limited function maps function to a sequence of complex coefficients \(\hat u_k\) satisfy

For any integer \(n\), the functions \(cos(2\pi nx), sin(2\pi nx), e^{2\pi inx}\) are all \(\Bbb Z\)-periodic(1-periodic). So in some math book the \(\hat u_k\) often denoted as:

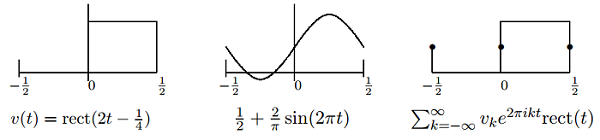

\(u(t)\) can be expressed as a linear combination of truncated complex sinusoids by the standard rectangular function as follows:

where

Complex Exponentials

A complex-valued function of the real variable \(x\) may be written as \(u(x)+iv(x)\)(u,v real valued), its derivative and integral with respect to \(x\) are defined to be

From this it follows easily that

The truncated complex sinusoids are orthogonal for \(k \ne m \in \Bbb Z\)

Fourier series energy equation

Fourier Theorem

More precision and interpretation

Let \(\{ u(t) : [−T/2, T/2] \to \Bbb C \}\) be an \(L^2\) function. Then for each \(k \in \Bbb Z\), the Lebesgue integral

exists and satisfies \(|\hat u_k| \le \frac 1 T \int |u(t)|dt < \infty\). Furthermore,

where the limit is monotonic in \(\ell\). Also, the Fourier energy equation (3) is satisfied.

Conversely, if \(\{ \hat u_k; k \in \Bbb Z \}\) is a two-sided sequence of complex numbers satisfying \(\sum_{k=-\infty}^\infty |\hat u_k|^2 \le \infty\), then an \(L^2\) function \(\{ u(t) : [−T/2, T/2] \to \Bbb C \}\) exists such that (3) and (4) are satisfied.

There is an important theorem due to Carleson, stating that if \(u(t)\) is \(L^2\), then \(\sum_k \hat u_k e^{2\pi ikt/T} rect(t/T)\)converges almost everywhere(convergence with probability 1) on \([−T/2, T/2]\).

\(L^2\) converge

A series is defined to converge in \(L^2\) if (4) holds. The notation \(l.i.m.\) (limit in mean-square)is used to denote \(L^2\) convergence, so (4) is often abbreviated by

The following example illustrate there is isolated discontinuity at \(t = −1/2, 0, 1/2\), the middle figure depicts a partial expansion with k = −1,0,1.

Reference:

- Alan V.Oppenheim. Alan S.Willsky. (1998). Signals and systems 2nd ed. (China: Prentice-Hall International,Inc)

- Hari Balakrishnan. George Verghese. (2012). 6.02 Introduction to EECS II: Digital Communication Systems. MIT OpenCourseWare (http://ocw.mit.edu/)

- Dennis Freeman. (2011). 6.003 Signals and Systems. MIT OpenCourseWare (http://ocw.mit.edu/)

- Robert Gallager. (2006). 6.450 Digital Communication. MIT OpenCourseWare (http://ocw.mit.edu/)

- Robert G.Gallager. (2009). Principles of Digital Communication (New York: Cambridge University Press).

- Harvey Mudd College Opencourse. E59 Administrative Information

- Terence Tao. (2009). Analysis I. Analysis II (Hindustan Book Agency)

A good person! More about the author →