Polar Coding Notes II

Random codes achieve capacity but their encoding and decoding is inefficient because they do not have a ‘nice structure’. Polar codes overcome this problem by splitting the channels into noiseless and useless channels. The noiseless channels preserve the encoding structure and therefore, for the information passed only over these noiseless channels, decoding can be done efficiently.

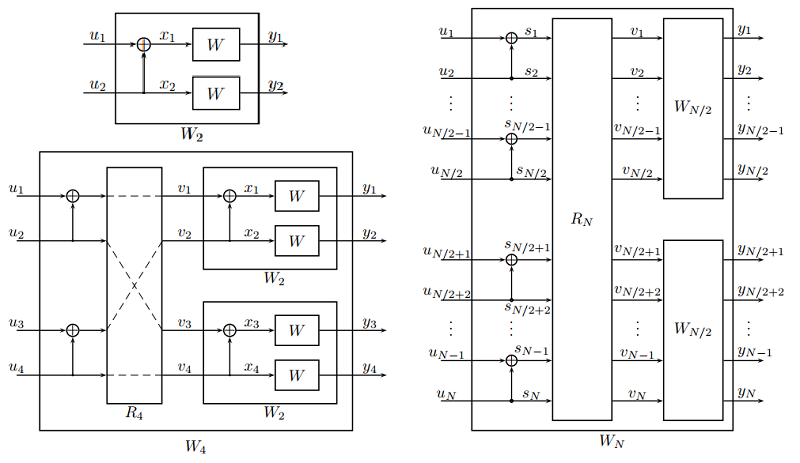

Channel Combining

Channel combining is a step that combines copies of a given B-DMC \(W\) in a recursive manner to produce a vector channel \(W_N : {\cal X}^N \to {\cal Y}^N\), where \(N\) can be any power of two, \(N=2^n, n\le0^{[1]}\).

The notation \(u_1^N\) as shorthand for denoting a row vector \((u_1, \dots , u_N)\).

The vector channel \(W_N\) is the virtual channel between the input sequence \(u_1^N\) to a linear encoder and the output sequence \(y^N_1\) of \(N\) copies of the original channel \(W\). \(W_1 = W\) is one copy of \(W\).

We use \(W^N : {\cal X}^N \to {\cal Y}^N\) to denote the vector channel between the input sequence \(x_1^N\) and the output sequence \(y_1^N\) of \(N\) copies of the original channel \(W\).

for any \(N = 2^n, n \le 0\),

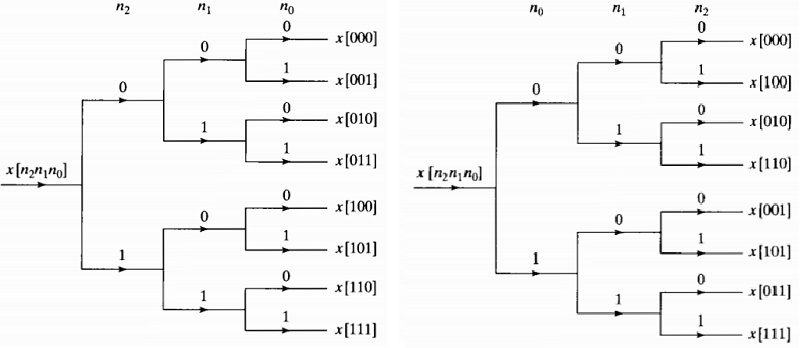

where \(B_N\) is a permutation matrix known as bit-reversal, \(F \triangleq \left[\begin{smallmatrix}1 & 0\cr 1 & 1 \end{smallmatrix}\right]\) and \(\otimes n\) is Kronecker power, which is a Hadamard transform.

The bit-reversal is shown as below from\(^{[8]}\)

Sort a data sequence in nomal order by successive examination of the MSB as the left in the picture.

Sort the sequence \(x[n]\) as the permutation matrix(sequence A030109 in the OEIS) order, such a separation of odd and even can be carried out by examining the LSB.

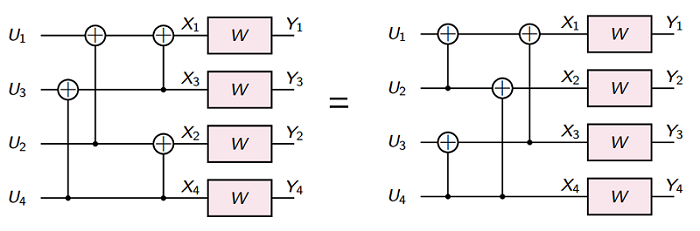

The recursive construction of \(W_N\) from two copies of \(W_{N/2}\) is useful for software and hardware\(^{[9]}\). But for hardware implementation, the “rewire” structure is more attractive:

We denote random variables (RVs) by upper-case letters, the coding scheme for \(U_1,U_2 \, \overset{i.i.d.}{\sim} \, Unif\{0,1\}\).

It is easy to see that \(U_1, U_2\) and \(X_1, X_2\) have a bijection, and further coupling this with the fact \(X_1,X_2 \, \overset{i.i.d.}{\sim} \, Unif\{0,1\}\). We have

and for \(U_1, \dots, U_N \, \overset{i.i.d.}{\sim} \, Unif\{0,1\}\), then \(X_1, \dots, X_N \, \overset{i.i.d.}{\sim} \, Unif\{0,1\}\),

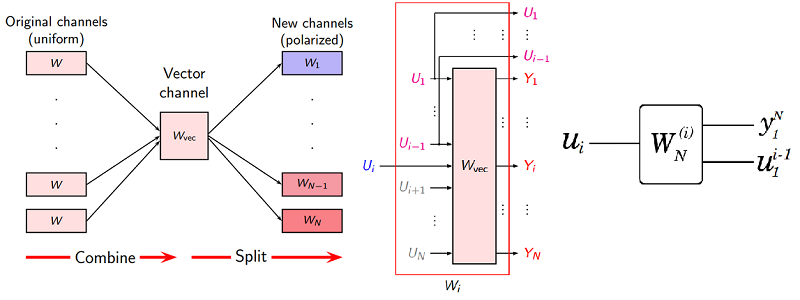

Channel Splitting

Channel Splitting is to split \(W_N\) back into a set of \(N\) binary-input coordinate channels \(W^{(i)}_N : X \to {\cal Y}^N \times {\cal X}^{i−1}, 1 \le i \le N\).

The transition probability of the \(W_N^{(i)}\) is defined as\(^{[1]}\)

For the \(u_i\) is \(i.i.d. , I(u_i;u_1^{i-1}) = 0\),

The transition probabilities are given by

For \(N=2\),

Below is from\(^{[1]}\)

Because, as both \(u_{2i+1,o}^{2N}\) and \(u_{2i+1,o}^{2N} \oplus u_{2i+1,e}^{2N}\) range over \({\cal X}^{N−i}\). And from (\(\ast\)), the sum over \(u_{2i+1,o}^{2N}\) for any fixed \(u_{1,e}^{2N}\) is

So we abtain

Reference:

- E. Arikan. Channel polarization: A method for constructing capacity-achieving codes for symmetric binary-input memoryless channels. IEEE Trans. on Information Theory, vol.55, no.7, pp.3051–3073, July 2009.

- Thomas M. Cover, Joy A. Thomas. (2006). Elements of Information Theory. John Wiley & Sons.

- David J.C. MacKay. (2003). Information Theory, Inference, and Learning Algorithms. Cambridge University Press.

- Erdal Arıkan. (2011.8.1). Polar Coding Status and Prospects. The IEEE International Symposium on Information Theory. ISIT’2011 Saint Petersburg, Russia.

- R. Pedarsani, S. H. Hassani, I. Tal, and E. Telatar. On the Construction of Polar Codes. Proceedings of IEEE International Symposium on Information Theory, Saint Petersburg, Jul. 2011.

- Eren Sasoglu. Polarization and Polar Codes. Foundations and Trends in Communications and Information Theory Vol. 8, No. 4 (2011) 259–381

- David Tse. EE376A/Stats376A: Information Theory. Winter 2016-2017. https://www.stanford.edu/

- Alan V. Oppenheim. Ronald W. Schafer. Discrete-Time Signal Processing, 2nd. Prentice Hall. 1999.

- E. Arikan. Polar codes: A pipelined implementation. 4th International Symposium on Broadband Communication (ISBC 2010) July 11-14, 2010, Melaka, Malaysia

- Vincent Y. F. Tan. EE5139R: Information Theory for Communication Systems:2016/7, Semester 1. https://www.ece.nus.edu.sg/

- Nikolaos Tsagkarakis. Design and Decoding of Polar Codes. Submitted on July 26th, 2011 in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Electronic and Computer. Engineering diploma degree.

A good person! More about the author →